· 5 min read

Engineering team develops ‘shipyard on a ship’

After months of product development, University of Nebraska–Lincoln engineers are leaving safe harbor to test their prototype on the open ocean.

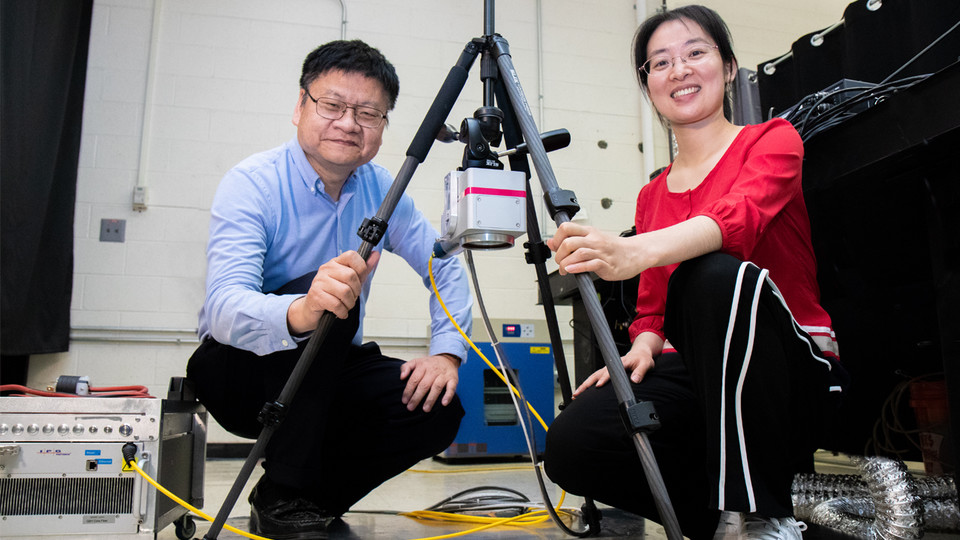

With support from the U.S. Navy’s Office of Naval Research, Nebraska’s Yongfeng Lu has developed a laser system that prevents and repairs corrosion on aluminum-sided ships. After accomplishing many project milestones — making the laser more portable, simpler to operate and safer than existing methods — his team is approaching its biggest debut yet.

This fall, they’ll test the laser on board a fully operational Navy ship. It’s the culmination of a competitive bidding process; in a pool with many teams from the private sector, the Nebraska team is one of just a few to reach the final testing phase.

“We are dreaming of a ‘shipyard on a ship’ concept,” said Lu, professor of electrical and computer engineering. “The upcoming test is a showcase for our technology and a final step. We’re excited to see the science lead to engineering improvements that add value to the real world.”

Aluminum ships are strong, but the conditions at sea, including prolonged exposure to saltwater and sun, can result in corrosion and cracks. To make repairs, crews must return to a shipyard, where damaged plates are removed and new ones are welded into place.

“This technology has the potential to save the Navy millions of dollars in shipyard time, as well as lost sea time,” said Airan Perez, corrosion and control science and technology program officer at the Office of Naval Research. “As the Navy expands its fleet of aluminum-hulled ships, this technology will become increasingly important.”

The Nebraska laser treats aluminum by heating targeted areas, a process that strengthens the microscopic boundaries around aluminum nanoparticles, which are more likely to corrode.

It is small enough to be suspended from a camera tripod and connects to a shoebox-sized controller with a fiber cord.

The laser generates its beam inside the fiber cord without using sensitive mirrors, making it more robust when operating outside of a controlled laboratory environment.

“We want our laser to work while a ship is in operation, because it reduces time and cost,” Lu said. “This also means we have to make our system very light, which is where other methods fall short.”

To achieve a lightweight system, the team stored all operating programs in microchips instead of a computer — a complex electrical engineering project that resulted in a small, easy-to-use prototype.

People operating the laser make just a few choices, such as selecting the thickness and type of material, and desired processing speed. With these inputs, the system then selects one of about 30 pre-programmed “recipes” with varying laser wavelength, power, frequency, beam-spot size, scanning speed, pitch and more.

“It’s simpler than using a cell phone, with just a few buttons to press,” Lu said. “We’re trying to minimize the burden to the user.”

As part of their product development process, the team is working with NUtech Ventures, the university’s technology commercialization affiliate, which has filed a patent application for the technology. The research team also follows market trends and monitors relevant companies, which influences the direction of their research.

When the team began research for their current prototype, the laser they needed wasn’t yet commercially available. But they continued to develop the underlying engineering principles for their solution while waiting for the commercial product. According to Lu, this approach helps them stay on the leading edge of innovation and remain competitive for funding opportunities.

“We develop processes based on lasers that will be available in the future, which gives us an advantage,” Lu said. “With our research, there will always be new materials and new ships coming out. A good engineering solution has to be evolving with the technology and user needs.”

Training the next generation

Lu’s future-focused mentality extends to his lab, which includes students ranging from high school to graduate school. The lab hosts two or three high school interns each year; these students work directly with lasers and learn how lasers modify surfaces at the nanoscale.

“We’ve been praised by the U.S. Department of Energy for our ability to introduce high school students to engineering careers and graduate programs,” Lu said. “We also focus on giving undergraduate students exposure to different fields and help them answer: What does it mean to be a programmer or an optical engineer?”

Graduate students, especially the lab’s doctoral students, take on leadership roles: managing projects, facilitating teamwork and helping build a positive work environment. Lu also emphasizes communications training for graduate students, who learn how to write regular updates to funding agencies and discuss progress during teleconferences.

“Our lab has many projects going on at once, and the students are the leaders,” Lu said. “We need even more leaders in this kind of science and technology, but I believe the future is bright.”