· 5 min read

Alumna’s career a monument to heritage, mettle

Editor’s Note — In observance of Women’s History Month, Nebraska Today is honoring Husker alumnae in March. Every Tuesday and Thursday, we’ll publish a feature story about Nebraska graduates making their mark on the world.

Throughout a two-decade career that recently saw her found a Manhattan-based engineering and architectural firm, Husker alumna Erleen Hatfield has proven herself the real McCoy.

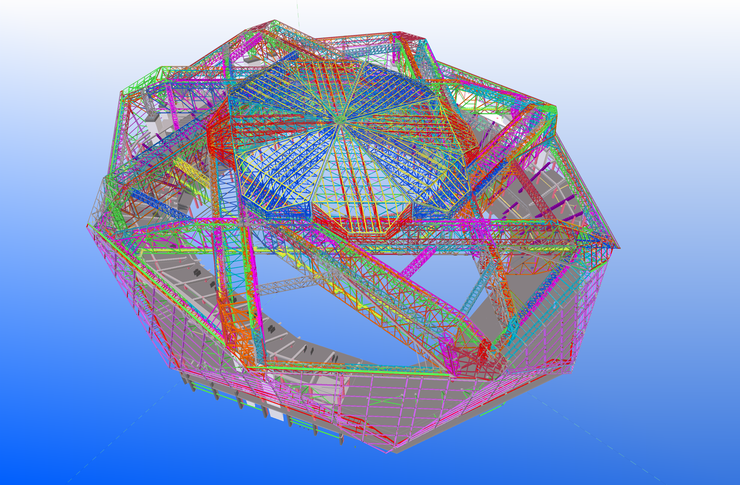

Befitting her name, Hatfield’s technical prowess informed the design of a revolutionary retractable roof that caps the Atlanta Falcons’ massive Mercedes-Benz Stadium and housed Super Bowl LIII.

Her fan-centric sensibilities and passion for athletics, borne of salad-day game days at Memorial Stadium, now grace The Vault that protects the home court of Husker hoops.

And her recollections of resilience amid tragedy, in the city that has become another home, occupy the halls and walls of the 9/11 Memorial Museum on which she worked.

But before reaching professional heights that have risen alongside her creations, the Lincoln native often watched day turn to night from inside Architecture Hall, absorbing design principles she would later incorporate worldwide.

“What I remember mostly fondly about my undergrad experience is just … learning about all these new things and the exploration of different ideas around architecture and design,” said Hatfield, who in 1991 earned her bachelor’s degree in architecture. “Meeting new friends and staying up late nights in studio (while) working on our projects. You develop a real camaraderie with your classmates.”

Rather than immediately pursue a career in architecture, Hatfield decided to follow a “natural progression” – and a talent for the math-dependent aspects of the field – by mastering in engineering and technology. After wrapping grad school at Nebraska, she represented a valuable double-threat: licensed architect and structural engineer.

Hatfield soon headed for Chicago before eventually landing in New York, spending a total of 22 years at the structural design firms Thornton Tomasetti and BuroHappold. Both allowed her to dig into the two adjacent compartments of her toolkit.

“What I’ve done in my career is to try to find a way to synthesize architecture and engineering,” Hatfield said. “I think my architecture background gives me the ability to really appreciate what the architects are trying to do from a design standpoint, and I think that appreciation shows up in the structures that we design – in a different way than if you just go through an engineering school and know that side of it.”

That dual perspective eventually propelled Hatfield onto projects such as Mercedes-Benz Stadium, whose eight-panel roof opens like the aperture on a 30-story camera lens.

“Not only had that never been done before, but the engineering was extremely complex,” Hatfield said of the stadium, which opened in 2017. “Early in the design, we were sketching all of these ideas with the architect, and we were challenging the status quo by looking at many different ways of opening the roof.

“We settled on the one that was ultimately built. Everybody loved it. And I remember talking to the architect, and him asking me very specifically, ‘Can you do this? Is this even possible? Is this crazy?’ (I remember) having those types of conversations and explaining to him, ‘Yes, we can figure this out. We can make it work.’”

Though the stadium may rank as Hatfield’s highest-profile project in the United States, she expressed equal pride in engineering the bones of Lincoln’s Pinnacle Bank Arena. She’s since taken in multiple games and concerts at the arena, which boasts an atmosphere that echoes one she remembers well.

“Being a Nebraska football fan since I can remember, and then going to school there and going to games, I do think had a big impression on my appreciation of sports architecture,” she said. “When I graduated from school, that was something I wanted to pursue.

“The idea that sports bring everybody together – a common experience with 70,000 or 80,000 other people – it’s really remarkable.”

As much as the state’s esprit de corps resonated with Hatfield, she also felt compelled to stretch – professionally and geographically. The decision, and the mindset, ultimately spawned opportunities to collaborate on projects from Dubai to Brazil.

“Try to have as many different experiences as you can,” Hatfield said of her early-career approach. “Always be pushing to do things that you can learn from but maybe make you uncomfortable. I really just wanted to have some broader experiences. I wanted to work on projects like tall towers and sports stadiums, because in the structural engineering world, those are some of the most challenging. To me, that was the most interesting.”

The prospect of entering a male-dominated field proved challenging in its own right, Hatfield said. She graduated as the lone women in her master’s cohort, an imbalance that she likewise encountered when entering the workforce.

“There were very few women at my level and even fewer women to look up to,” Hatfield said. “So it was always (a matter of) trying to do as much as I could to gain respect and to show people what I was capable of. I think things are a little bit easier and better today. There certainly are more women in the field.”

As managing partner of the recently formed Hatfield Group and a past director of the Structural Engineers Association of New York, Hatfield has herself emerged as a guiding star for young women entering the industry. Her longstanding involvement with organizations such as the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation, which promotes the neglected legacy of women in the field, also reflects her interest in clearing paths to it.

“Being involved in different women’s organizations is really about trying to help other women coming up, because when I was, there wasn’t a lot of help,” Hatfield said. “It’s centered around trying to show the accomplishments of women in the industry: architects, engineers and contractors. We’re trying to show that women have done incredible things. They’ve just gone unrecognized.”