Calendar Icon

Nov 20, 2015

Person Bust Icon

By Karl Vogel

![]() RSS

Submit a Story

RSS

Submit a Story

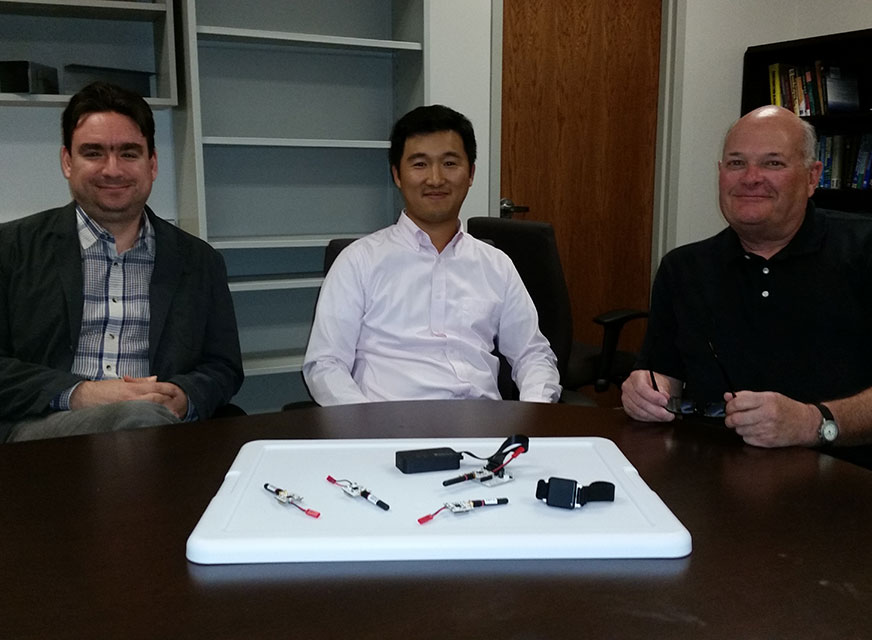

Inspired by a former graduate student who is a construction contractor and iron worker, three UNL engineers are hoping their upcoming project will help make construction job sites safer.

By revealing potential and hidden hazards in a changing environment and studying the behaviors of construction workers, Changbum Ahn, Terry Stentz and Mehmet Can Vuran are hoping to save lives and prevent injuries through a three-year, $350,000 grant from the National Science Foundation.

“OSHA has repeatedly identified construction fall accidents as the number one construction site safety concern, and the trades that have the highest rates of construction fall injuries and fatalities are iron workers and roofers,” said Stentz, associate professor of construction engineering and management. “We figure we can gather objective data, analyze it and maybe see our way through to a better way to prevent fall accidents.”

Ahn, an assistant professor of construction engineering, said getting to know Cory Lyons made the project even more personal. Lyons, a general manager with Topping Out, Inc., of Davis Erection Co. in Lincoln, told the team tales of steel erection job-site hazards and spurred them to begin doing research.

“He made it clear that the important thing is identifying the safety hazard on the job site and that the essence of this project should be trying to learn how humans react to safety hazards,” said Ahn.

“We had some hypotheses and made some assumptions in the past, but we didn’t have a really clear picture that allows us to analyze the individuality of each worker. Once we know that, we can better utilize the information in terms of estimating the existence of many types of hazards.”

Identifying workplace hazards has traditionally fallen on human inspectors. But, Ahn said, those inspections aren’t always sufficient because some hazards aren’t easy to spot and the environment on job sites changes daily.

“(Inspectors) can see physical dangers, but sometimes the hazards also can include interactions with a physical environment and a human worker’s behavior and those are often hidden,” said Ahn, an assistant professor of construction engineering.

“We are looking to the hazard that may cause a fall and we are looking into the gait of the construction worker. If a hazard exists, it may cause some abnormality in walking motions.”

To better study the construction worker on the job site, the team will rely on the expertise of Vuran, an associate professor of computer science and engineering who has plenty of experience studying cranes – more specifically, using sensors to collect data about whooping cranes.

To monitor the birds, Vuran and his team created some of the first avian wearable technology devices – backpacks that included an accelerometer, a gyroscope, a GPS and a magnetometer to measure the posture and movement of the cranes. The data gathered was transmitted through a cellular chip via a wireless provider.

“We learned that the cranes are a little different than other migratory birds, they fly in families rather than flocks – two adults and a chick,” Vuran said. “Within that study, we were also looking at the behaviors of the birds. Combining field observations with the data we were getting, we were able to identify the behaviors of the birds.

“This project started with Dr. Ahn inquiring about whether we could use similar techniques for iron workers.”

As with Vuran’s study of whooping cranes, this project will likely require innovation in the creation of wearable sensing devices and the software programs used to measure the behaviors of individual construction workers.

“The technology we are hoping to develop has shown preliminary success in allowing us to tailor our algorithms to detect abnormal responses,” Vuran said.

This, the team hopes, could lead to new training methods that could not only protect the workers, but also make construction projects more productive and less expensive.

“The economic cost of construction as it relates to accidents is enormous,” Ahn said. “If you have to stop work at a job site, that can be a big cost and worker’s compensation is huge. It’s in the billions of dollars.”

Stentz also said Lyons helped the team see much more than a cost benefit for construction companies.

“We started this based on the workplace tribal knowledge and experience of Cory. He’s been an iron worker for 20 years and knows the work inside and out,” Stentz said. “He knows it’s not fun to work on a construction site when you’re worried about safety. If there’s a way we can improve how workers behave, control the hazards, lower their stress level and raise their confidence in the safety system, which pays off in fewer accidents and lower costs.

“In the end, improved construction site safety helps families. Companies actually hire families. And the company and the family both want their construction worker to be safe and come home every day.”

By revealing potential and hidden hazards in a changing environment and studying the behaviors of construction workers, Changbum Ahn, Terry Stentz and Mehmet Can Vuran are hoping to save lives and prevent injuries through a three-year, $350,000 grant from the National Science Foundation.

“OSHA has repeatedly identified construction fall accidents as the number one construction site safety concern, and the trades that have the highest rates of construction fall injuries and fatalities are iron workers and roofers,” said Stentz, associate professor of construction engineering and management. “We figure we can gather objective data, analyze it and maybe see our way through to a better way to prevent fall accidents.”

Ahn, an assistant professor of construction engineering, said getting to know Cory Lyons made the project even more personal. Lyons, a general manager with Topping Out, Inc., of Davis Erection Co. in Lincoln, told the team tales of steel erection job-site hazards and spurred them to begin doing research.

“He made it clear that the important thing is identifying the safety hazard on the job site and that the essence of this project should be trying to learn how humans react to safety hazards,” said Ahn.

“We had some hypotheses and made some assumptions in the past, but we didn’t have a really clear picture that allows us to analyze the individuality of each worker. Once we know that, we can better utilize the information in terms of estimating the existence of many types of hazards.”

Identifying workplace hazards has traditionally fallen on human inspectors. But, Ahn said, those inspections aren’t always sufficient because some hazards aren’t easy to spot and the environment on job sites changes daily.

“(Inspectors) can see physical dangers, but sometimes the hazards also can include interactions with a physical environment and a human worker’s behavior and those are often hidden,” said Ahn, an assistant professor of construction engineering.

“We are looking to the hazard that may cause a fall and we are looking into the gait of the construction worker. If a hazard exists, it may cause some abnormality in walking motions.”

To better study the construction worker on the job site, the team will rely on the expertise of Vuran, an associate professor of computer science and engineering who has plenty of experience studying cranes – more specifically, using sensors to collect data about whooping cranes.

To monitor the birds, Vuran and his team created some of the first avian wearable technology devices – backpacks that included an accelerometer, a gyroscope, a GPS and a magnetometer to measure the posture and movement of the cranes. The data gathered was transmitted through a cellular chip via a wireless provider.

“We learned that the cranes are a little different than other migratory birds, they fly in families rather than flocks – two adults and a chick,” Vuran said. “Within that study, we were also looking at the behaviors of the birds. Combining field observations with the data we were getting, we were able to identify the behaviors of the birds.

“This project started with Dr. Ahn inquiring about whether we could use similar techniques for iron workers.”

As with Vuran’s study of whooping cranes, this project will likely require innovation in the creation of wearable sensing devices and the software programs used to measure the behaviors of individual construction workers.

“The technology we are hoping to develop has shown preliminary success in allowing us to tailor our algorithms to detect abnormal responses,” Vuran said.

This, the team hopes, could lead to new training methods that could not only protect the workers, but also make construction projects more productive and less expensive.

“The economic cost of construction as it relates to accidents is enormous,” Ahn said. “If you have to stop work at a job site, that can be a big cost and worker’s compensation is huge. It’s in the billions of dollars.”

Stentz also said Lyons helped the team see much more than a cost benefit for construction companies.

“We started this based on the workplace tribal knowledge and experience of Cory. He’s been an iron worker for 20 years and knows the work inside and out,” Stentz said. “He knows it’s not fun to work on a construction site when you’re worried about safety. If there’s a way we can improve how workers behave, control the hazards, lower their stress level and raise their confidence in the safety system, which pays off in fewer accidents and lower costs.

“In the end, improved construction site safety helps families. Companies actually hire families. And the company and the family both want their construction worker to be safe and come home every day.”

Submit a Story