Calendar Icon

Apr 07, 2020

Person Bust Icon

By Karl Vogel

![]() RSS

Submit a Story

RSS

Submit a Story

RELATED LINKS

A parking lot on Nebraska Innovation Campus is the site of a newly and quickly created hand sanitizer production facility that aims to meet the burgeoning needs of Nebraska healthcare workers and others on the frontlines of the COVID-19 outbreak.

What started with two members of the Nebraska Ethanol Board – Hunter Flodman and Jan tenBensel – looking to make a difference during this crisis turned into a partnership that has brought together the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and the College of Engineering, Nebraska’s ethanol industry, and the State of Nebraska.

Green Plains Inc., and KAAPA Ethanol are donating ethanol, while BASF, Cargill and Syngenta are providing other required chemicals. Sapp Bros. is collecting ethanol from the plants, storing it at its facilities and delivering small batches to the west side of the Food Processing Center at NIC, where the sanitizer solution is mixed and bottled.

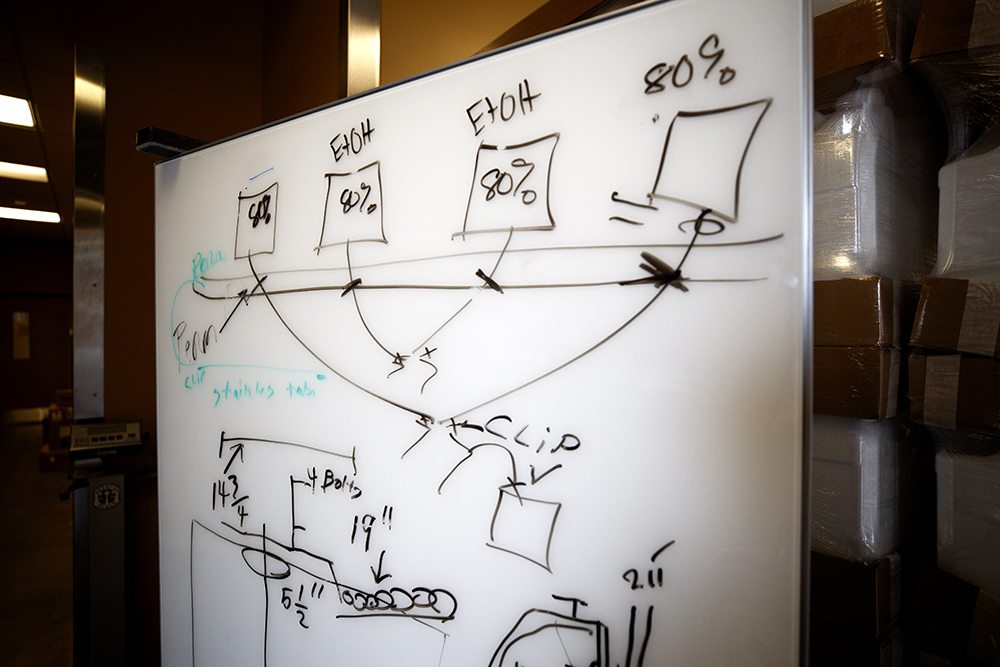

After a week of sleepless nights and dedication to the cause, the plant is up and running and churning out sanitizer that Flodman, assistant professor of practice in chemical and biomolecular engineering and technical advisor on the Nebraska Ethanol Board (NEB), hopes will make a big difference in battling the virus.

“Over the last week, everybody’s worked extremely hard to make this happen,” Flodman said. “The reason we did this is because we want to help.”

The six-person crew making the sanitizer includes Flodman and tenBensel, who is board chair for the Nebraska Ethanol Board and a farmer from Cambridge, Nebraska, and four employees from the Food Processing Center – executive director Terry Howell, pilot plant manager Russell Parde, research technologist Sarah Herzinger, and product developer Julie Reiling.

“The partnership with Terry Howell and the Food Processing Center is key. Without Terry and his team , we would not have been able to make this happen,” Flodman said.

Flodman also noted several other members of the university staff that were integral in getting the project started on an accelerated time table, including prototype design specialist Leonard Akert, associate director of EHS Joel Webb, assistant director of building systems maintenance Gabe Hampton, and many others who contributed to the project.

Numerous companies and state agencies that generously donated time, material, and resources to the project should also be recognized, including Aurora Coop; BASF; Beatrice Scale Company; Bosselman Enterprises; Cargill; CKS; Greenfield Global; Green Plains Inc.; HowatRisk; Johnson Matthey; KAAPA Ethanol; Market Actives; Nebraska Innovation Campus; Renewable Fuels Nebraska; Sapp Bros.; Syngenta; and The American Cleaning Institute. State of Nebraska agencies involved include the Nebraska Department of Administrative Services, Nebraska Department of Correctional Services and the Nebraska Ethanol Board.

Many entities in the medical and healthcare industries have run out of sanitizer or have seen their supply dwindle to a desperately low amount due to a national run on hand sanitizer that saw demand for the product in February increase to a level 14 times greater than two months earlier. That demand led to both extreme shortages and severe price hikes.

And, because millions more Americans are working from home or self-isolating to help prevent the spread of the virus, demand for fuels that include ethanol has dropped, leaving Nebraska’s ethanol producers to face unusual challenges in the energy markets.

“After hearing about shortages of hand sanitizer, we hoped we could find a way to overcome some of the obstacles our fuel-grade ethanol producers were facing, including navigating the FDA’s regulations,” said Flodman.

It all came together quickly – from Mark Riley, College of Engineering associate dean of research, contacting the Food Processing Center on March 29 to the first batches of the sanitizer bottled during a test just seven days later.

A total of 1,200 gallons of sanitizer was produced during the April 5 test run, but Flodman isn’t sure how much they’ll be able to produce in a day once the production process is finalized.

“It depends on so many factors, the biggest being how they (the State of Nebraska) want us to package it,” Flodman said. “If it’s 250-gallon containers, we can make a lot. If it’s 1-gallon containers, that process takes longer.”

When the site is operating at full capacity, more workers might be needed to help. For now, Flodman said, there’s still a lot to be done.

“April 5 was Day Zero and April 6 was Day One. We’re still figuring out the best way to produce batches and to fill and package containers. We’ve got to get all of that determined before we have volunteers help with the project.”

Submit a Story